The Road of Mastery

Nadia Comăneci, compounding, and the joy of practice

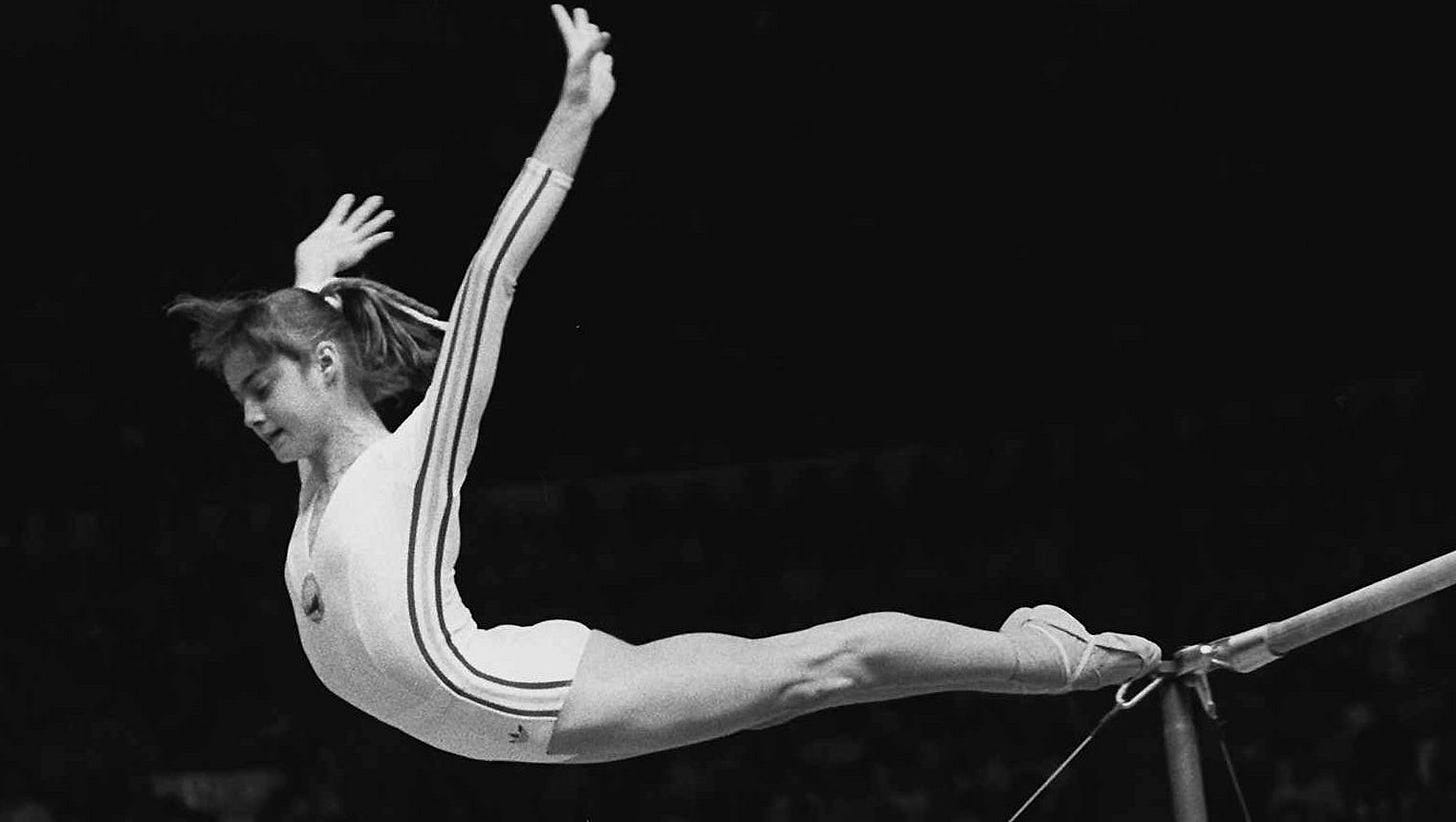

The 1976 Montreal Olympics is forever remembered for an iconic moment: when the first perfect “10.00” was awarded in gymnastics.

Before Nadia Comăneci, perfection in the sport of gymnastics was presumed to be unattainable. The scoreboard for the Olympic competition was designed to hold only three-digit scores, at maximum a “9.99.” After Nadia finished her routine, confusion rippled through the crowd as the scoreboard displayed a “1.00.” Then, gasps and stunned applause as they realized what had just happened. Nadia went on to earn six more perfect “10s” en route to five Olympic medals in Montreal, three of them gold.

So what made her special? If you have never seen footage of her routine, you can find it here. Certainly the steely, faultless quality of her gymnastics hinted at something sublime and superhuman. But she was human, flesh and bone. And just a 14-year old girl at that. She reached the Olympics the same way other athletes did. By spending weeks and months in the gym perfecting difficult routines on their apparatus.

It is interesting to hear what Nadia herself said differentiated her from her peers:

“My coaches told me that I was the kind of child that when they were telling me ‘today we have to do five routines on balance beam,’ I might do seven. And I think in time, that little bit every day was like building a house, bringing one brick more than everybody else.”

“One Brick More”

What separates the excellent from the merely good, in any domain? What distinguishes the virtuoso from the adept?

Innate physical and mental abilities clearly play an outsize part. As do environmental factors such as facilities, equipment, coaching and family support. And we cannot overlook the role of chance and luck - of being the right person at the right time and place.

But what if two people possessed identical assets: bodies, talent, environment and opportunities? Then there would be only one remaining variable driving differences in outcomes: time spent in practice.

Whoever puts in more hours of training and practice ends up going farther. Largely because benefits compound over time.

The same mathematical law of compounding from finance applies more generally in life. Small inputs, when invested with consistency over a long time horizon, yield exponentially growing results like a snowball rolling down a hill. The eventual outcome ends up being far greater than seemed obvious at the outset.

Nadia Comăneci’s metaphor of building a house provides a good illustration of this. With each extra practice run, she was adding “one more brick” than her peers. Each practice run, like a single brick, might not have seemed like much in the moment. But these compounded day to day, week to week. By the time the Montreal Olympics came around, Nadia had a substantially bigger house than everybody else.

So if the secret to success lies in compounding over time, then the next question is: why are some people able to keep at their pursuit for so many hours longer than their peers? What enables such individuals to continue chipping away at their goal in the face of challenges, frustrations and boredom?

The key turns out to be nothing other than a love of practice itself.

One can picture Nadia going for extra run-throughs of her routine simply because she loved practicing the routine. Of course, sitting in the back of her mind - like any elite athlete - must have been the dream of winning a gold medal one day. But we often forget that the few brief moments on the podium constitute less than 0.001% of an athlete’s years-long career. The other 99.999% of the time is filled with the mundane grind of training and practice.

George Leonard, who has written extensively about his journey to become a fifth degree black belt in Aikido, writes:

“How do you best move toward mastery? To put it simply, you practice diligently, but you practice primarily for the sake of the practice itself. Rather than being frustrated while on the plateau, you learn to appreciate and enjoy it just as much as you do the upward surges.”

-George Leonard, Mastery

Appreciating the plateau

Leonard’s point about appreciating the plateau is critical. If you have ever attempted to master something - a sport, an instrument, a language - you would know that progress is often not a smooth linear function of effort. Spending 100 hours trying to get better at something doesn’t necessarily yield 100 hours worth of results right away.

This is particularly true during the later phases of a student’s journey. Being a beginner is easy and fun. Teachers are attentive and supportive. Progress comes fast and easy. The path is clearly laid out. But when the novice stage ends is when the real work starts.

For the last fourteen years, I’ve been a student of an acrobatic Afro-Brazilian martial art called “capoeira.” It is a difficult martial art to master, demanding strength, balance, flexibility, timing and strategy.

I remember when I realized I was no longer a beginner at capoeira. My teachers spent less time correcting me or telling me what to work on next. I wasn’t gaining new skills as quickly as I had become used to. It became less obvious how to go to the next level.

This is the point where capoeira students diverge onto different paths. Some lose interest, and stop. Others - often the most enthusiastic and hard charging beginners - hit a wall as overtraining catches up, bringing injury or burnout.

Even the few who stick around long enough for the plateau split into different camps. There are those who appear content with the results they have achieved so far. They still go through the motions at practice, but without looking to improve or to change anything in particular. Then there are those who get bored with the monotony of the plateau. Craving novelty, they keep restlessly scanning the far horizon for new directions and ideas, neglecting to plumb the depths of what they already have right where they are.

And then, there are the ones who continue to strive for perfection, mindfully, patiently and steadily. Who find ways to enjoy the plateau: relishing each extra repetition, each timeless moment of practice. They come to recognize what George Leonard is alluding to when he says:

“The essence of boredom is to be found in the obsessive search for novelty. Satisfaction lies in mindful repetition, the discovery of endless richness in subtle variations on familiar themes.”

Why do these lessons of mastery matter? Because our world is increasingly enamored with instant gratification and overnight results. We lionize the champion, the expert, the phenom without thoroughly appreciating what it took them to get there. We see geniuses like Nadia Comăneci performing at an impossibly high level without fully recognizing that such mastery comes after a long journey. One which cannot be survived without cultivating an intrinsic appreciation for the each speed bump and plateau along the way.

The ethos of mastery is the antidote to the quick-fix, instant-results mindset. What takes longer to build, brick by painstaking brick, is ultimately more worthwhile and enduring.

There is no secret to excellence. We must learn to love the process. To love the practice for its own sake, even if it doesn’t come with a gold medal in the end. Becoming a master in any discipline is never guaranteed. And that’s ok.

The joy that comes from being on the road of mastery is its own sweet reward.